Have you ever wondered what it’s like to start your own nonprofit organization and grow it successfully for 20 years? Last month we posted the first part of our interview with Cooperative for Education founders Joe and Jeff Berninger. They talked about what inspired them to improve education in Guatemala, how they came up with the model for CoEd’s first program, and what finally convinced them to launch a nonprofit.

This month, Joe and Jeff explain how their parents reacted when they left the corporate world and give us a glimpse into all that it takes to get a fledgling nonprofit organization off the ground.

Listen podcast-style to the snippet below or scroll down to read the full transcript. (Scroll down regardless to see photos.)

Note: If you’re on mobile and don’t want to listen in the SoundCloud app, click “Listen in browser.”

Joining in late? Listen from the beginning.

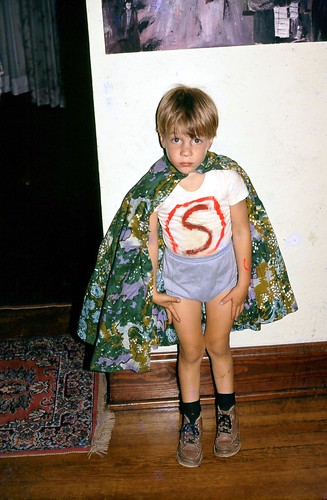

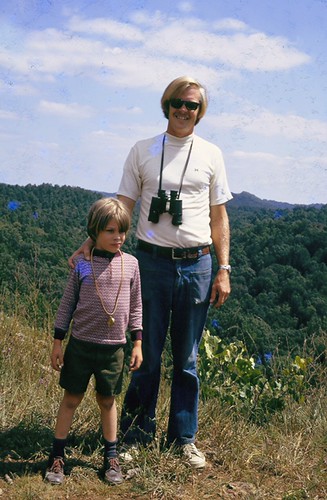

Joe (center), Jeff (right), and their older brother John (left)

Courtney: What did your family say when you both told them what you were planning to do?

Jeff: Well to wrap up the Johanna story, as soon as my dad met her it checked off that box of getting on with my life, because first of all he liked her, and he knew that he had done some non-traditional things, like moved out to a farm and all of that. So it completely satisfied him.

Joe: Yeah, and I think our parents saw it as— We were raised to believe that if you can do good, if you are in a situation where you have the opportunity to do good, you have to do it. You know? So if the lady walking in front of you crossing the street falls down in front of you it’s yours to help her. We saw in Guatemala, I think, that we had solutions in our minds to the problems that we saw in front of us.

Jeff: Mhm.

Joe: And we were drawing— You know we both were in the business world, had spent time in the business world in Cincinnati, Jeff at P&G and me at IBM, earlier. And we started to see that: Hey, you know there are some things that we can do to organize this system and these processes to make a difference in these schools. They don’t have books now and the quality of education is really low. We can make it. We see that we can do it to give them books. And by 1997, once we started the nonprofit, we saw that there were donors that were willing to back us up with that. That they liked the basic concept: they liked basic business concepts put into place in the third world to create self-sufficiency and create sustainability and create better education and so forth. That had traction up here. So suddenly we found ourselves in the position of like: Hey, there is a good here that can be done and we’re being called to do it. So let’s do it. We have to do it. And that was part of number two also, because I think that at least our mom, as far as the family goes, once she kind of understood it in that context she was like: “Go do it! Go and do what you guys need to do; we support you one hundred percent.” Dad was a little slower to come around.

Jeff: He was slower to come around but he was always the leader—as you tell the story a lot of times—well, since he was a teacher he always knew the kids in school whose families had fallen on hard times. And he would, after we would sell some of our cash crops and stuff in the fall, coming up near Christmas, there was always a big portion of it that he would collect together, and he’d put it in a few envelopes and we would just drive down the road—around town and different places—and he would just put them in people’s mailboxes. And also, I was just recalling this as well, that for Christmas Eve—our kids have no concept of this, but—we would go visit the elderly. But people really kind of, that are on these farms, but like stuck down in the middle of nowhere. And we were kind of afraid of them and stuff like that. One lady had this big crooked toe and stuff like that. But anyway, I think they really imbued a sense of, like Joe said: Go above and beyond. Don’t just make your donation; really go seek the people who need help, or who can benefit from your presence and your help. So I think they were pretty quick to embrace the project. I think they figured if it failed we’d come back and do something else; they knew that we were successful in the corporate world. I think the main stumbling block—and you probably felt this too from Dad at times—was getting married, basically. Once we had both found someone and gotten married he was more…

Courtney: So he was concerned that if you were too focused you wouldn’t get married?

Joe: I think a lot of it was that my parents struggled. My dad was a teacher, my mom was a homemaker. Five kids, lived on a farm. My parents always struggled economically, you know. We never went hungry but there was always: my parents sold walnuts to make twenty bucks, we sold loads of firewood, and my dad was always trying to make a little money here, a little money there. So when we got corporate jobs in big corporate America and had health insurance and benefits and salaries and all this kind of thing—Dad—to him, we had made it. He had done his job as a parent and we were well placed. And then the talk of giving that up and leaving all that and going and doing some other kind of squirrely, you know, nonprofit thing that’s gonna last a couple years, and then having to come back and try to do something else, like—he was concerned that we were getting our lives off track, I think. At first. And then once I think he saw that we were making a success of it and doing okay with it and it was growing, he jumped on board and came along.

Jeff: And that was part of the struggle at first, was just to simply grow it. You know we talk a lot about sustainable projects and now we’re talking about sustainable organizations. And for us at that time a sustainable organization was one that we would be able to afford to run and raise a family. So I think that was one of our principle motivators behind growth at that time, other than the obvious motivator of wanting to help.

Joe: Mhm.

Jeff: But you can’t help if you run out of money. You can, but—

Joe: You can’t sustain it. A key part of sustainability of having a nonprofit is having some way to, you know, I guess you can be where you have another basis of income, or eventually you have to work for your own nonprofit, and it has to be big enough to pay you.

Jeff: And pay you in a way… Because we had gone back to living on, like church mice, like the college way or the traveler’s way—like when Joe travelled around the world. You know, where you live on a dollar a day, kind of thing. So we had adopted lives where, you know, we both lived in the offices in our respective countries of the project. So yeah, you had your living room and then where the TV went, the administrative person went.

Joe: Yeah. In early CoEd, that’s right. We had like a 12-step commute to work because we both lived at the office in our respective countries.

Courtney: For how many years was it like that, where you were living in the office?

Jeff: I mean we kind of hit our targets…for me of getting…when I got married I moved from the office to a house, so that was it.

Joe: ‘96 to ‘02

Jeff: Yeah, Johanna wasn’t going to live in that office with me. But actually we were going to live in the house behind it, because that had come available, because we didn’t think we needed that much space, and then we were like: No, that’s too close to work.

Joe: So for me it was six years, for you it was probably more like four. You got married in 2000. I was married in ’02. But before that, before we were married, we lived at the office.

Jeff: Yeah, ’99…yeah, so three years.

Joe: You never left work. I remember that, you never left work. You were always: you’d take a break, get back on your computer, work some more, make some calls—

Jeff: Right, because you still lived—you still lived in that office right up until you got married.

Joe: Until ’02, yeah.

Joe: Jess and Anne, they would come in to work downstairs and I’d come down—my bedroom was right next to my office.

Jeff: Yeah. Joe’s bedroom was next to the office and when Johanna and I would come in town we slept on the third floor. We actually had Cristina in a crib and we had two twins pressed together to make a king I think, because you couldn’t fit anything larger than a twin up in the attic. And then Joe had to work with a donor on the cheap to get a bathroom installed up there. We said: We don’t need a shower, because you could always go downstairs and take that, but just a bathroom, you know, so you’re not trying to walk down—

Courtney: every time.

Jeff: Yeah. That’s kinda the way we made it work. There was just no money for that. I actually still have the Excel sheets from our accounting, and an entire year would fit almost on a screen—a little longer than a screen and maybe a couple tabs, one for Guatemala and one for the US—and that was our accounting.

Joe: We wanted the absolute most money to go to the kids in Guatemala. So like, we cleaned—I was the janitor, I cleaned the toilets at the office. I cut the grass. I did all the repairs. So we never, never thought a penny should go to anything like that.

Jeff: And we didn’t get paid until— We often got paid six months in arrears because we didn’t pay until all the bills were well-paid and enough checks had come in.

Courtney: So you only paid yourselves bi-annually?

Joe: In the first couple years. If there was any money at the end.

Jeff: Because we would have a proposed salary in our budget, but we didn’t know if we would fundraise that much. We didn’t have a reserve or anything.

Joe: Our goal was to make $18,000 a year, which is, that’s like basic survival.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks